Freedom—October 16, 2019—Boaters recreated as usual at Ossipee Lake Natural Area this summer. Most stayed in the water, but among those using the shore, a majority took heed of the boundaries between the shoreline that’s open for recreation, and the shoreline that’s not.

It’s been ten years since the state made a bet that preservation and recreation could coexist at the property, and it’s a bet that has paid off. Rare plant colonies are coming back, and self-regulation by the boating community has largely worked to keep order.

It wasn’t always like this. For more than 30 years, the Natural Area was an orphan under the state agency DRED, which permitted the property’s globally rare plants and ancient artifacts to be trampled by uncontrolled recreation.

After the state in 2004 said it was willing to lease part of the property to Ossipee for a town beach that would also be open to the general public, environmentalists and the lake community said enough was enough. The ensuing fight lasted four years, until a change in DRED’s leadership brought a moment of calm and new thinking.

The new thinking was to thoughtfully balance recreation and preservation at the site. It was a radical notion—a kind of environmental Hail Mary pass—that would require environmentalists to give up part of the property in order to save a majority of it; and require boaters to accept limits on their use of the shoreline in order to prevent rafting from being banned altogether.

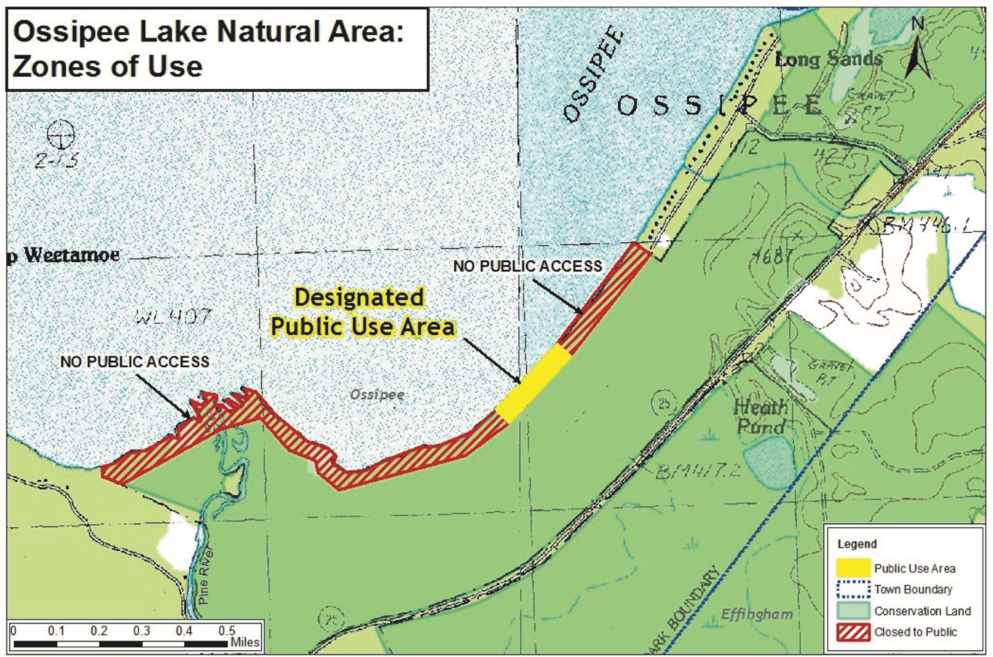

How DRED’s new leaders successfully brought these competing interests to the table, while also obtaining the support of groups like the Marine Patrol, is a tale for another occasion. Suffice it to say that after a brief closure of the property so that a management plan could be written, the Natural Area reopened in the summer of 2009 with a large section of the shoreline open to boaters, and the rest off-limits to all but state rangers and researchers.

A “working group” of lake stakeholders was established as part of the plan, and it continues to meet annually with the Natural Heritage Bureau to discuss how things are going. And things are going pretty well, according to the Bureau’s administrator, Sabrina Stanwood.

In emails with Ossipee Lake Alliance, Stanwood said the site’s natural communities are recovering, and rare plant populations have increased since the areas outside the designated recreation area were closed. The recovering plants include the colorfully-named Grassleaved Goldenrod and Hairy Hudsonia, and, in a surprise discovery, the Long‐Tubercled Spikesedge (Elocharis), last seen at the site in 1962 and thought to have been extirpated.

In an update to the management plan, Stanwood said the property currently contains 12 protected plant species and three exemplary natural community systems. It’s also mapped as being among the state’s highest-ranked habitats in the Wildlife Action Plan published by New Hampshire Fish & Game.

One of the goals of the boating community representatives in the working group was, and remains, to enhance the state’s communications plan with on-site interactions with other boaters about rules compliance.

There have been ups and downs to that strategy, but by all accounts, boater-to-boater interactions have been effective, as evidenced by the site’s environmental recovery. But there is still frustration that state enforcement isn’t always available when it’s needed.

Richard Lover is an original, and continuing, member of the working group from the boating community. The Milton resident spends most summer weekends at the Natural Area with his family, socializing with friends made at the site over the course of many years.

“I can honestly tell you that the general boating community does follow most of the rules on their own after being educated and made aware of what the rules are,” he told Ossipee Lake Alliance.

“My biggest issue that I had back then and still have today is the state’s lack of enforcement,” he said, adding that the state is “woefully understaffed” in Ranger Services and Marine Patrol, adding that judges have been reluctant to enforce tickets when tickets are appealed.

Dennis Gould is another original member of the working group from the boating community. An active lake volunteer who helps collect water samples and protect loons during their nesting season, he spent years influencing boaters to comply with the Natural Area’s site regulations and organizing spring clean-ups at the site.

But no longer. He dropped out of the group several years ago, saying he was frustrated by the unwillingness of the state’s current leadership to consider opening additional parts of the preserve for low impact family recreation.

“There was always a hope that if the boating community lived by the rules and didn’t hurt the rare plant life, especially in the Short Sands area, that we may eventually open up some of the small pockets of sandy areas between the open area of Long Sands and Pine River,” he said in an email.

Stanwood says that while the state is open to discussing the possibility of additional recreation areas, the location identified by Gould isn’t suitable because it’s part of the “sandy pondshore community” that makes the shoreline unique. It was closed when the management plan went into effect in 2009.

Since then, patrolling Forest Rangers have found boaters at that site and had to ask them to leave. It is also the area where the thought-to-be-lost Elocharis plant was discovered this year. For those reasons, there is no plan to consider opening those specific areas, Stanwood said.

In regard to enforcement, much has improved in a decade, even if it’s not always evident. Prior to ten years ago, there were no site-use regulations for the property, and Marine Patrol took the position that what happened onshore was the responsibility of Park Rangers, not boating safety officers.

DRED responded that there weren’t enough Park Rangers to patrol the area even if they had a boat to provide access, which they did not. The territorial impasse was largely resolved by the adoption of the management plan and the participation of the two organizations in the working group collaboration.

Marine Patrol Captain Tim Dunleavy is another original working group member who still serves on the panel. He says that confronting boaters who break the Natural Area rules—such as pulling their boat ashore instead of anchoring offshore—is part of what his officers do in the regular course of enforcing boat safety laws at the site.

He said the role that boaters have played in self-regulation has been significant, and the presence of his officers during busy times is a deterrent. He also believes there is an evolution in progress in the willingness of judges to take infractions seriously when a ticket is appealed. But he agrees that more can be done.

“We do what we can with what we have,” he said in a phone interview, noting that it’s a “real challenge” to recruit officers.

“Would I like to have more Marine Patrol officers to put on the case? Absolutely.”

Forest Rangers are also in short supply. Patrols were reduced to less than four days in 2018, the last reporting period, due to fire details. On the positive side, Natural Heritage Bureau’s Stanwood says the state deployed an automated camera at the site this year and plans to add a second next season.

As the Ossipee Lake Natural Area management plan enters its second decade, it’s not hard to understand why most view it as a success, but also a work in progress. It was not so long ago, after all, that the only options on the table were to allow the property to be destroyed, or to ban rafting entirely.

Instead, boaters next year will again be able to use a large stretch of shoreline and recreate in the sandy offshore waters, and environmentalists will continue to take pride that rare plants and natural communities will survive to be studied for years to come.

As boater Richard Lover puts it, “It’s not perfect, but it’s the best of all the ideas and suggestions the various stakeholders brought to the table.”