INDIAN MOUND CAMPS OFFERED FOOD AND LODGING WITH A TASTE OF HISTORY

Article by David L. Smith

Ossipee Lake Report

April-June 2006

In the 1920s and ‘30s, it was one of the lake’s most popular destinations. A place where a traveler on the White Mountain Highway could stop for dinner and spend the night, or a vacationing family could enjoy a week or more swimming, boating, and playing tennis.

In the 1920s and ‘30s, it was one of the lake’s most popular destinations. A place where a traveler on the White Mountain Highway could stop for dinner and spend the night, or a vacationing family could enjoy a week or more swimming, boating, and playing tennis.

As recently as the 1990s, it was still possible to poke through the remains of the Indian Mound Camps on Route 16B near the Indian Mound Golf Course. A stone’s throw from the road, but hidden by the woods, sat the collapsed shell of the resort’s recreation lodge, its entryway twisted but still upright; a front desk and a wall of wooden mail slots evidence of a once bustling past.

The last traces of the Indian Mound Camps were swept away by development in 2000 when a boat storage building was constructed at the site. But thanks to memories and memorabilia, it’s possible to step back in time and get a sense of what it was like to visit during its heyday.

Family Business

Indian Mound Camps was a family business operated by Ellery Briggs and his wife. It sprawled over both sides of the highway, where the golf course is now located, and extended to the lake. There was a restaurant and gift shop, a filling station, tennis courts, and cabins, both on and off the lake.

Transient visitors were always welcome, but the Briggs family had a loyal following of vacationers who returned annually. Long-time Ossipee resident Fenton Hodge said his mother, now in her 90s, worked at the resort and can still recall the regular visitors who arrived at the Center Ossipee train station from Boston and beyond.

Transient visitors were always welcome, but the Briggs family had a loyal following of vacationers who returned annually. Long-time Ossipee resident Fenton Hodge said his mother, now in her 90s, worked at the resort and can still recall the regular visitors who arrived at the Center Ossipee train station from Boston and beyond.

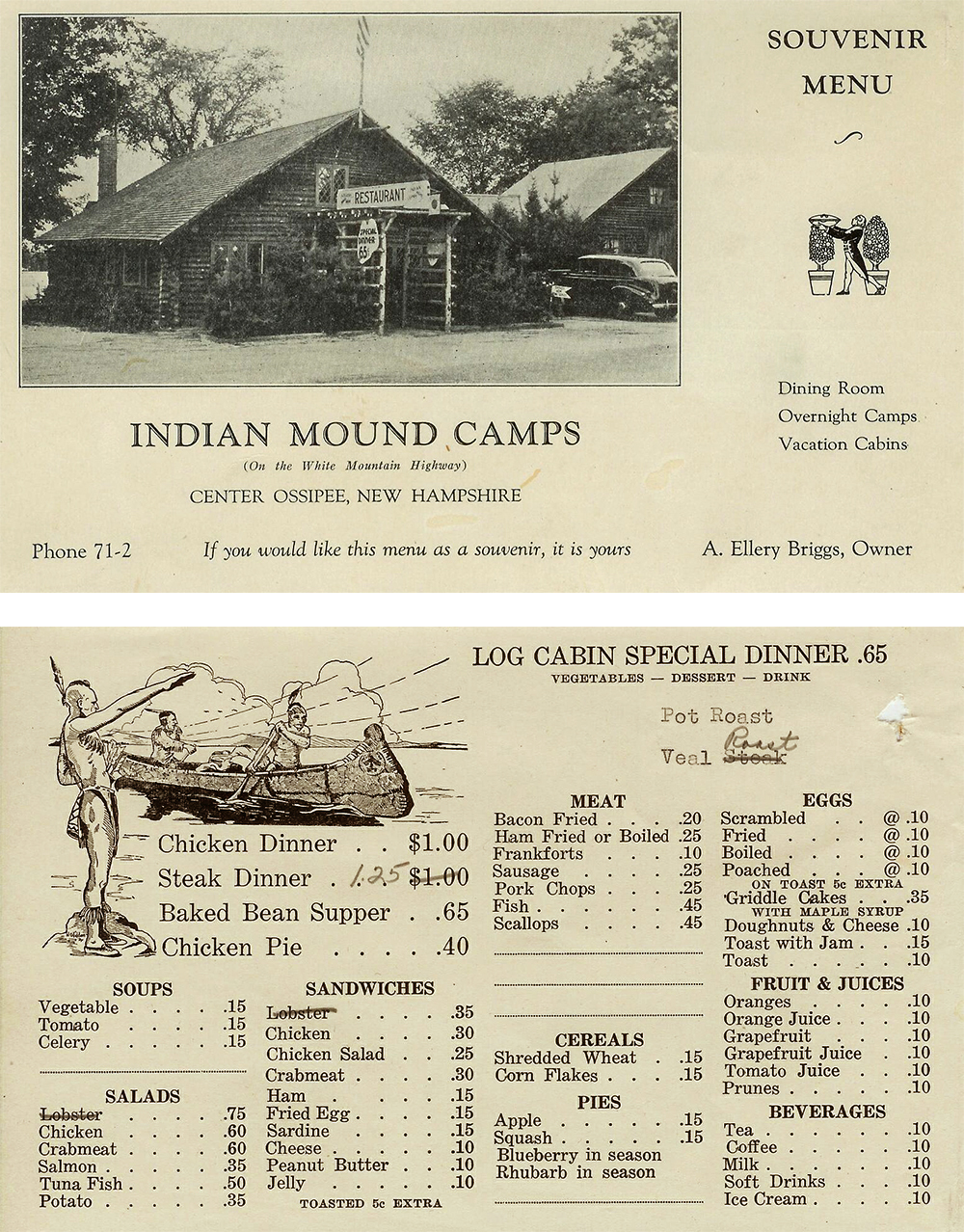

If you were stopping for a meal, the pot roast special was 65 cents, or you could spring for a steak dinner for $1.25. A handwritten note on an Indian Mound Camps menu we acquired this year indicated that the kitchen had run out of lobster.

Could the food have been an attraction? Ossipee Selectman Harry Merrow says he can’t remember a lot about the resort, but does recall having a sandwich and a birch beer there with his grandfather during the 1940s, when he was a youngster. He says the building was quite rustic and there was a piano in the main lodge.

According to one of the resort’s brochures, visitors spending the night could stay in a “cabin in the pines” that included “electric lights, running water and a soft restful bed” for two dollars, double occupancy. Lakeside, vacationing families had their pick of larger cabins for $30 a week, including all recreation options.

History in the Air

The lake and the mountain scenery weren’t the only attractions, however. The scent of history was in the air in the form of the “Indian Mound”. Legend held that it was constructed of circular chambers holding the remains of 800 Native American souls who were interred sitting upright.

In addition to the burial mound, visitors could find a wolf trap (an Indian pit used to snare animals) and the site where Captain John Lovewell conducted his ill-fated Indian raid of 1725, according to a vintage brochure.

While Indian Mound Camps brimmed with stories of Indians and settlers, many of them were more colorful than correct. According to historian and writer Tom McLaughlin, an excavation in the 1940s showed the burial mound was actually a naturally-occurring glacial formation. Moreover, historians long ago concluded that Captain Lovewell’s raid may have been planned on Ossipee Lake, but was actually fought on Lovewell’s Pond in Fryeburg.

The Final Days

By the 1940s, Indian Mound Camps was in decline. The owners had grown old, and the war years may have taken a toll on their business. While the reason the couple closed the resort is unknown, what happened next is clear. Instead of selling the property, the Briggs family simply closed it up and walked away.

Vandals stripped the buildings of their fixtures and furnishings, and neglect finished off everything else. Over time, the buildings disintegrated and collapsed.

After his wife died, Ellery Briggs lived with his daughter, Alma, and her husband, Clyde Drinkwater, next to the resort in the white colonial-style farmhouse that still stands at the edge of the golf course.

The Drinkwaters ran the Indian Mound Dairy, which was in the cinder block building that also still stands on Route 16B next to the farmhouse. By the mid-1960s, however, the dairy was gone, and the surrounding property was sold and developed for golf.

Indian Mound Camps has vanished, but its colorful advertising copy survives. Who can resist the lure of ancient burial chambers and ghost soldiers on the lake? Certainly not us, which is why we’re pleased to bring you the following glimpses of the world of Ossipee Lake’s Indian Mound Camps in the 1930s:

Excerpts from the Brochure

The cabins in the pines will easily give comfortable lodging to two, four or six people. They are equipped with electric lights, running water, and soft restful beds. During the winter months they are steam heated or whenever the weather is uncomfortable. The toilet rooms in the Lodge have hot and cold water, shower baths, lavatories and flush toilets.

The cabins on the lake accommodate easily six or eight people. Everything necessary for housekeeping is furnished except silver and linen. These cabins are modern, and of course have running water, flush toilets, screened porches, and electric lights.

The Indian Mound on This Farm

The Indian Mound, or burial place, of the Pequawkets is located on the beautiful intervale south of Lovewell’s River and west of Ossipee Lake. It was originally 25 feet high, 75 feet long and 50 feet wide. In or about the year 1800, Drs. McNorton of Sandwich and Boynton of Tamworth made an opening in the mound sufficiently large to ascertain the internal structure.

The Indian Mound, or burial place, of the Pequawkets is located on the beautiful intervale south of Lovewell’s River and west of Ossipee Lake. It was originally 25 feet high, 75 feet long and 50 feet wide. In or about the year 1800, Drs. McNorton of Sandwich and Boynton of Tamworth made an opening in the mound sufficiently large to ascertain the internal structure.

They found the bodies placed in a sitting position around a common center and packed hard against each other, yet reclining toward the center and facing outward. When one circle was completed, another was made outside it until the base was large enough to commence to another tier above the first one.

Just enough earth was used to fill between the tiers. The excavators estimated that not less than 800 bodies were buried in this mound, and from appearances the mound had been 1,000 years in the making. The decimation of the tribe by the pestilence of 1616 broke up the practice of interment here.

The land at the western end of Ossipee Lake, much of which is within the boundaries of the farm, was a spot often frequented by both Indians and white men. Between 1650 and 1660 the English built here so that the Ossipee tribes might aid them in their war against the Mohawks.

Lovewell’s River

The river that runs through the northern boundary of this farm is named Lovewell’s River for Captain Lovewell of Dunstable, who used this spot as the base for his ill-fated scalp hunting trip in 1725.

On April 16th of that year, as soon as the snow was out of the woods, Captain Lovewell left Dunstable with a company of about fifty men. Between April 22nd and May 5, the party rebuilt the old English fort originally built about 1660 and destroyed about 1676. The lines of the old ditches may be seen to this day.

A few men had turned back, due to illness on the trip north, but leaving ten men at the fort, Lovewell set out with thirty-five.

On May 8th the whites came into contact with the Indians. Lovewell’s men did not know it, but the Indians knew their exact strength, for when they had first sighted the Indians they had taken off their packs and put them in a pile. An Indian scout worked his way to the packs and counted them.

The fight was a bitter all-day affair. Lovewell and eleven of his men were killed. Three were so badly wounded that they died on the way back to the fort. One man, badly wounded, crawled to a canoe, rolled into it, and made his way to the fort to report that there had been a massacre. The guard at the fort started back for the settlements. When the survivors returned, they found the stockade abandoned and no provisions.