From the Archives: A Public Beach in a Natural Area

Part 5: Managing Expectations

Anyone who has worked with state employees knows they come from a variety of backgrounds. Even in that diverse work environment, Don Kent stood out.

For a decade or more, Kent worked at Walt Disney Imagineering, where he was responsible for environmental research and planning for Disney’s massive land holdings. Among his tasks was protecting more than 60 species during the construction of Walt Disney World and Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

In November, 2007, Kent became Administrator of the Natural Heritage Bureau, making him the state’s point person for juggling the competing interests of biologists, bureaucrats, elected officials, boaters, and conservationists.

Don Kent is credited with crafting the coalition that made the Natural Area management plan a reality. Photo: YouTube

To this potentially career-building or career-ending role was added the job of writing the Natural Area’s first management plan. A briefing summary on the situation at that point might have read as follows:

“The state bought the property without a plan for it, and for 38 years allowed its irreplaceable environmental resources to be trashed. That failure resulted in public clashes between boaters and property owners, conservationists and local elected officials, and all of them against the state. The divisions among stakeholders are raw and deep, and a solution is nowhere in sight.”

In Concord and on the lake, the consensus was that the Natural Area problems would never be solved, no matter who was in charge. Kent was determined to change that perception.

To dispel what he called “a lot of misinformation,” he and State Environmental Specialist Melissa Coppola collated years of research to produce a definitive report documenting the site’s “non-renewable, fragile and rare” natural resources.

Then, perhaps channeling marketing’s “rule of three” from his private sector experience, he established three options for the management plan: Step away and do nothing, close the site permanently, or balance recreation and preservation. Predictably, consensus formed around the least extreme option of balancing competing interests, which became the goal.

Bringing the competing interests to the table, however, meant first getting them into the same room. To do that, Kent made an offer no one could refuse: Participate in a “Working Group” of lake stakeholders and help write the management plan, or sit it out on the sidelines. The gambit worked; all sides joined in.

In June, 2008, a draft management plan written by agency officials with stakeholder input was ready for release. But first, Kent gave everyone a dose of reality. No one would be getting everything they wanted, he said, and preservation, not recreation, was his agency’s primary responsibility.

There was more. After an initial period during which the state would create wide public awareness of the plan, it would be up to local resources—meaning conservationists and boaters—to make it work.

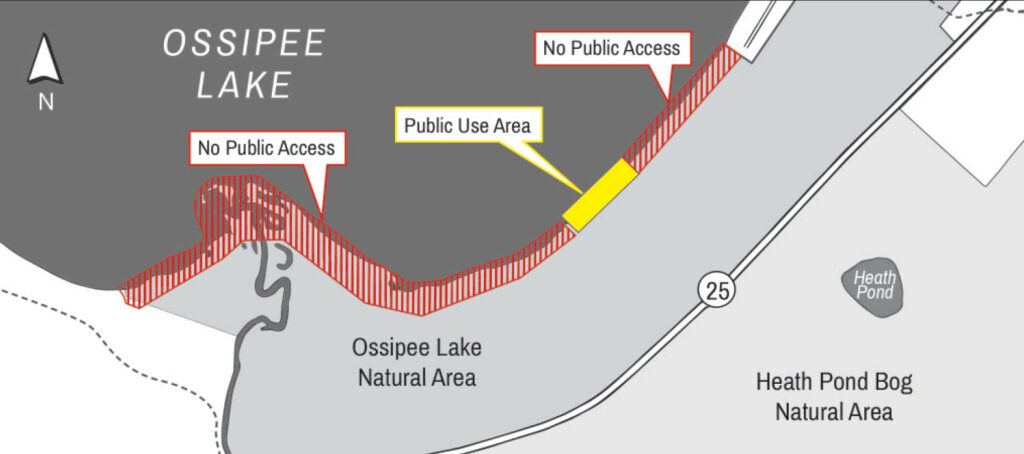

The site’s public use area was established in 2009 and remains the same today. Alliance/GMCG/DNCR pamphlet.

The gist of the plan was simple. Some 1,500 feet of shoreline would be open for low impact recreation, and the rest of the property would be off limits. The remainder of the document was largely boilerplate regulations pertaining to all public lands, including prohibitions against dogs, fires and camping.

Planning for implementation began on November 14 at Ossipee Town Hall, under Kent’s direction. DRED was well-represented, as were Marine Patrol and various departments of DES.

Representing the boating community were Richard Lover of Milton, Allen McKenney of Hudson, and John Panagiotakos of Freedom. Also in the room were representatives of Ossipee Lake Alliance, Green Mountain Conservation Group, Long Sands Association and the three local town conservation commissions.

Lakefront Landing Marina and Campground represented the business community, and John Shipman and Sheila Jones represented the towns of Freedom and Effingham. Ossipee was represented by Harry Merrow.

It was a battle-scarred group reflecting the diversity of opinions that had steered the debate to that point. As they eyed one another warily across the meeting room tables, they got to work.

Many issues received quick top-line resolution, and then foundered. For example, it was easy to get consensus that boaters who violated the site rules should be held to account. But by whom?

DRED’s Forest Rangers and Marine Patrol officers agreed they were the logical candidates, but both groups came prepared with a list of role conflicts, staffing issues and legal constraints that ensured neither could be fully counted on.

Swimmer safety? Water quality? The role of local officials? The questions to be addressed were logical and obvious, but solutions were as hard to come by as state funding.

When frustrations boiled over, Kent reminded the group that “all eyes were on the project,” as the state’s first such effort.

“We’re not here to look backward and assign blame to boaters or to the state for the damage that has already been done,” he said. “Our job is to look forward and make this plan work.”

State officials and local volunteers celebrated completion of the Natural Area’s first management plan with a clean-up day on May 15, 2009. Alliance Photo

With failure not an option, hardened positions gradually softened, aided by Kent’s regular reminders to the group that success required boaters and conservationists to find common ground and work together. The meetings continued through the winter.

By the spring of 2009, they began to wind down. That May, Kent led DRED employees and Working Group members on a boat trip to pick up litter and haul away winter debris from the site. Then in June, the property’s first-ever management plan went into effect.

At its core was the premise that boaters would self-monitor and encourage others to comply with the site regulations in order to keep the shoreline partially open for recreation. It was a kind of state-sponsored Hail Mary Pass.

No one was sure it would work, but there was a sense of accomplishment and optimism among the Working Group participants. With Commissioner Bald’s commitment and Kent’s leadership, they had seemingly accomplished the impossible.

Documenting the moment, Ossipee Lake Alliance took a picture of the clean-up team at the site, and devoted an entire issue of its newsletter to salute the groups that had participated.

Ironically, that month, June 2009, marked the 40th anniversary of the state’s purchase of the property from White & Sawyer.

Next: Keeping the Management Plan Afloat

“At its core was the premise that boaters would self-monitor and encourage others to comply with the site regulations in order to keep the shoreline partially open for recreation. It was a kind of state-sponsored Hail Mary Pass.”

Really? …it’s no wonder there is such little faith in government.

As noted in the discussion phase of developing this Management Plan, access to the selected shoreline of the OLNA is a State granted priveledge, not a right, and as part of the allowance of this priveledge, it is the obligation and responsibility of the users to follow the established use regulations, basically self policing. When this is not accomplished, certain priveledges will be rescinded.

Knowing human nature, the notion that self-policing would ever work is naive. Drive on any freeway at any time of the day to understand the inability of people to follow rules. If there is no system in place to enforce regulations, then there is little hope of compliance. Rescinding access to the beach is meaningless without enforcement.