Effingham—March 27, 2024—In the spring of 2021, an Effingham business posted a sign on Route 25 saying it was looking for clean fill. A truck driver working at a near-by commercial development stopped to say he had plenty of it. An agreement was struck and the fill was delivered.

It’s a transaction that likely happens every day, but this particular one has sparked a debate about what some say is a loophole in New Hampshire’s environmental regulations. The loophole is this:

While the state closely regulates what can be done with soil that is known to be contaminated with petroleum-related chemicals, it allows the owner of a contaminated site to decide if soil from elsewhere on the property can be moved to another location.

No testing is required, no minimal amount of separation from the contaminants needs to be documented, and no report needs to be filed. The property owner can simply make the decision.

As a result, when Ossipee Lake Camping Area accepted the assurance of Meena LLC that soil from the contaminated Boyle’s Market gas station site was safe because it wasn’t from where the contamination was found, the parties may have been exercising questionable judgement, but the transaction was permissible under state law.

That would not be the case in neighboring states, according to a review of their environmental regulations.

In Maine, for example, what is known as “surplus soil,” such as the excess from an excavation at a contaminated site, may only be repurposed on-site, sent to a licensed facility for treatment, or used to build roads and parking lots, according to Mathew Burke, Senior Environmental Hydrogeologist with Maine’s Bureau of Remediation and Waste Management.

Effingham whistleblower Martin Casey was the first to report that soil removed from the former Boyle’s Market gas station property was accepted as fill by Ossipee Lake Camping Area on Leavitt Bay. The transaction appears to be legal under the state’s current environmental laws. DES Photo

When it comes to soil from a current or former gas station, Maine’s regulations prohibit material from being removed and used in a residential setting, including a campground, even if the source site was never documented to contain contaminants, according to Burke.

The regulations in Massachusetts are a bit different, but have similar intent.

In the Bay State, the boundaries of a disposal site—the place where a release of oil or hazardous materials above reportable concentration has occurred—must be defined in a site plan. It is possible to remove soil from the property and reuse it elsewhere, but only if it is removed from outside the boundaries identified in the site plan.

Soil determined to be above reportable contamination levels may not be moved offsite. But the “similar soils” regulation allows soil with only trace levels of petroleum contaminants—that is, a level below reportable concentrations—to be moved if the contamination level does not exceed the level of contamination at the receiving location.

Ossipee resident Dana Simpson is a retired environmental official who has overseen more than 1,000 hazardous waste site remediations. He says the question about whether the Meena gas station soil transfer was permissible skirts a larger issue.

“Soil from the gas station should never have gone to a campground, whether it was presumed to be clean or not,” he told Ossipee Lake Alliance.

In a letter to Effingham officials, Simpson called the soil transfer “an egregious violation of the public trust” and “an example of poor judgement.”

“The soil should always be presumed to be contaminated, and even if not, to avoid any doubt, and in the interest of caution, it should be tested and sent to an authorized disposal facility with proper documentation.”

Burden of Proof Standard

Simpson’s observation echoes Connecticut’s regulations, which require an owner of a partially contaminated site to provide evidence that what is planned to be removed from the property is not contaminated.

Like Massachusetts, Connecticut requires a site plan of the contaminated property that documents where the contaminants are and the location where the soil to be removed and relocated is coming from.

Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection official Mark Lewis, a Supervising Environmental Analyst at the Bureau of Water Protection & Land Reuse, characterized the process as a “duty to determine via investigation,” and he likened it to the scientific method used in medical analyses.

“The property owner creates a hypothesis that the soil to be removed is clean, and then conducts testing designed to support or refute the hypothesis,” he said in a phone interview.

“In all events, the responsibility and the burden of proof are on the property owner to create certainty about the actions being planned.”

That is not the case in New Hampshire, according to N.H. DES official Robert Bishop.

“We do not have a regulation indicating that an entire parcel is considered potentially contaminated when contaminants are found on the property,” he wrote to Ossipee Lake Alliance.

“There are also no regulations indicating distance from a sampling location where contaminants were detected.”

When Gasoline Enters the Ground

Geoscientist Dr. Robert Newton has studied the Ossipee Aquifer extensively. His YouTube video calling the Meena site the “worst possible location” for a gas station has garnered more than 1,100 views and continues to be featured in the debate over the proposed development.

Newton points to the fact that gasoline consists of more than 150 different chemicals, some of which are soluble in water, others of which evaporate quickly when exposed to air. He says that when gasoline enters the ground, each chemical may react differently.

In the unsaturated zone above the water table, vapors can move both laterally and vertically in the gas phase and may even condense back into a liquid form far from the site of the original spill.

“The naphthalene found at the [Meena] site when the previous gas station was removed in 2015 was likely residual material that was stuck there because it is a ‘sticky’ compound,” Newton says.

“It may still be there, but the less sticky compounds have likely been transported away by the groundwater.”

One of the principal determinants of how far chemicals can move away from a spill site is the permeability of the soil, and the soil at the Meena site is highly permeable.

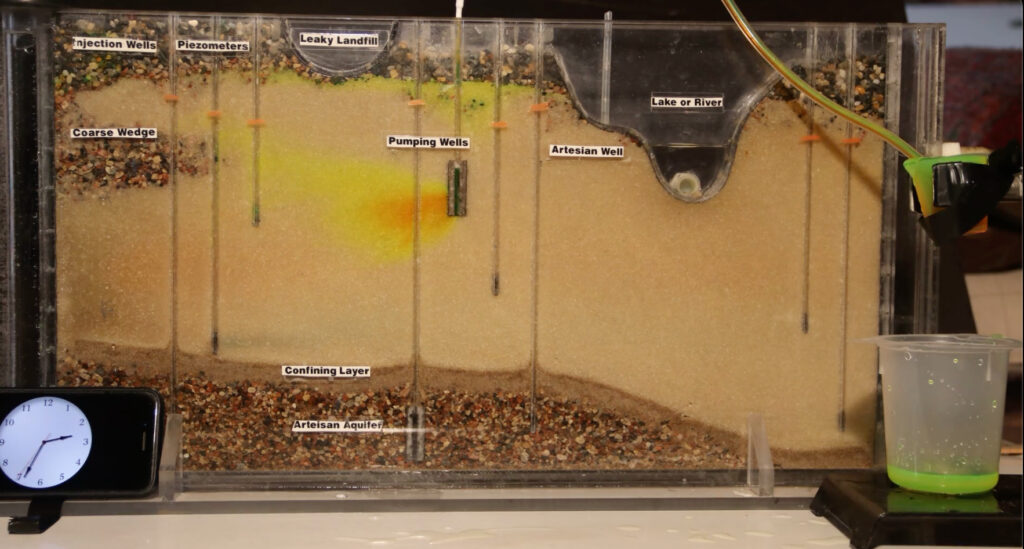

To demonstrate the point, Newton created a video model showing how a non-reactive dye moves through sand. He says a subsequent sampling of the site where the dye was introduced would show the contaminant was gone, but it in fact has just moved along with the groundwater.

“In the case of the Meena site,” Newton says, “only the naphthalene was left behind while the other gasoline constituents either were broken down or traveled further downstream.”

“There is no data to answer which hypothesis is correct, which is why it is so troubling that Meena was able to remove material from its contaminated property without testing or a site plan,” Newton concluded.

In a screen shot of Dr. Newton’s model, a tube from the well runs to a small beaker on the ring stand. A syphon is used to simulate pumping the well, and the height of the small beaker establishes the pumping rate. The overflow allows the head to be constant and is captured in the larger beaker at the bottom. There is a change in color when the contamination plume gets to the well. Click here to view the animated video.

For 3 years (since 2021), the Effingham Board of Selectman have been asked by the public about the “Dirty Dirt” in BOS meetings. Since suspected hazardous waste sand has been dumped on the shores of Ossipee Lake, none of the Selectman have responded or acted. Perhaps it’s because previous Selectman have stated on the record that they gave Meena permission to install tanks illegally before going through the process that the rest of the public is required to go through. If local boards will not represent the public’s interest and their laws and their health, who will? Transparency, Integrity, Courage. Please.

Maybe a naive question but if the soil at the Meena site is contaminated wouldn’t that mean that the groundwater is already contaminated? The former owners/gas stations, at the Meena, location have been providing gas for many years. Based upon Dr. Robert Newton’s extensive analysis I would expect well water to already be full of contamination from prior gas station operation.

The Meena site, before the new Underground Storage Tank system, UST, were illegally installed, (for the area where old tanks and pumps were located), was under asphalt. Once excavated to facilitate the tanks removal in 2015, and when recently, excavated, 2021, to install new UST’s, the area where contaminated soils occurred was subjected to stormwater leeching down from the surface in ares where new paving has yet to be placed.

It is possible contamination may have found its way into the groundwater and ultimately migrated in a northerly direction, potentially contaminating dozens of wells north of the site. Unfortunately, the state nor the Town of Osdipee has even considered this possibility, nor has a collective water sampling of any of these wells been performed by either the State, (NH DES), or the Town of Ossipee. While the possibility of contamination is not high, it may be well advised for home owners in those areas north of the Meena site extending to the two Bays, to perform a comprehensive well water test.